Alexithymia is common with traditionally masculine men

“It is hard for me to say stuff like that.”

A recent clinical encounter reminded me of an important point about the way many modern men experience their emotions and needs, and how this can have a dramatic impact on relationship quality and lead to all sorts of confusion and conflict. I have seen the themes unfold in similar ways in many different couples; I recreate a typical scene below.

Alicia*, a nurse practitioner in her mid-40s, entered individual therapy with a doctoral student of mine. She was experiencing high levels of distress, much of it centered on her relationship with Frank, her husband of five years, who worked as a carpenter. Alicia described Frank as having been warm and loving during the first few years of the relationship, but things had gotten bad over the past few years and now he was cold, detached, and prone to angry outbursts. The description was such that we felt it was crucial to see Frank and get his take on the situation. Although Frank was initially very reluctant, he eventually agreed to come in and share his version of reality.

At our initial meeting, he was guarded and resistant. However, by empathizing with his concerns about being ganged up on, and showing him quickly that we could help, by explaining to him why his relationship had gone sour and how it might get better, he bought into the process. It turned out that the therapy was quite successful in turning the vicious cycles around, and much greater levels of relational satisfaction and well-being returned to Frank and Alicia in a month or so.

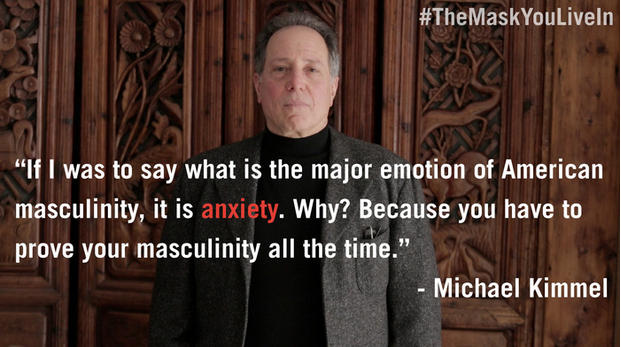

One major issue that had to be addressed early was a fairly common one, especially with “traditionally masculine” men. It is what former APA president Ron Levant called “normative male alexithymia.”(link is external)

Before I define the term, consider the following exchange which took place during our first session: I had met individually with Frank for about 30 minutes, and had a sense of where he was coming from. When we came together for the couples work, I said to both partners, “One of the most important things for this relationship is to understand where each of you is coming from at an emotional level—that is, the level at which you feel appreciated, admired and loved, or vulnerable, rejected and hurt. Let’s take some time and share what each of you is experiencing at that level.”

After a brief pause, Alicia started in.

- Alicia: I guess I can go first. There are many times I don’t feel that Frank cares about me or respects me. I ask him to respect my office space, but he comes in and leaves it a mess. I ask him to let me know when he is coming home, but he forgets to call. He knows I like hearing he loves me, but he rarely says that. Early in our relationship I felt he wanted to hold and protect me, and that he wanted to honor me. There were times that he could even be vulnerable with me. But now—now I just feel this coldness from him. And when I ask him to do things, like tell me when he is coming home, he just lashes out at me.

- Me: Thank you, Alicia. You made clear some of the ways you used to feel valued and how that filled a need in you. And you noted that it has drifted and there are several times you experience Frank as being withholding or devaluing you in some way. Frank, I know from our earlier conversation, you also have lots of feelings about this relationship… (I indicate the floor is his.)

- Frank: Well, you know, the relationship was better earlier. And now, not so much. She says I don’t call, but I usually do. And I do tell her I love her…sometimes. (Frank stops there, despite my nonverbal cues to go on.)

- Me: And, Frank, if you look deep inside, how do you feel about how she treats you? What do you feel about her and when does it feel better or worse?

- Frank: It’s okay, I guess. I mean, I don’t know. The relationship—sometimes she annoys me. And sometimes I yell. But that doesn’t happen all the time. The relationship is OK. Not great, but OK.

I glance over at Alicia, who is shaking her head in frustration. To speed the process along, I engage in a technique I call “directive empathy.” Directive empathy uses the skills of the clinician to guide the empathetic understanding of the individual’s inner experience and quickly conceptualize the situation. In this case, directive empathy was applied to the couple. It is crucial that this be artfully done. Because I had chatted with Frank, I knew where he was coming from. Although he was initially guarded, I was able to strike a good relationship with him fairly quickly, which allowed me to say things directly in a way that, if not done right, could have been very threatening.

- Me: Let’s take note of the differences in Alicia’s response and Frank’s. Frank, you had a much more difficult time talking about how you feel than Alicia did, didn’t you?

- Frank (nodding): I don’t talk much about my feelings. People say I am cold, that I don’t have feelings.

- Me: I think you have feelings, Frank. In fact, my gut tells me you feel things very deeply. However, you don’t know how to put your feelings into words. You have been socialized to be a “man,” which to you means that you are independent and strong, that you don’t need anyone else, and are not vulnerable. It means that if you get a feeling that you were criticized or rejected, a feeling that you were hurt, you can’t stay there. Instead, you either get angry or withdraw or tell yourself you can handle it and it isn’t even that big of a deal. That is why, even though there are rich feelings in there, you can’t really talk about them, not even privately to yourself. And it is especially difficult to share them publicly and tell Alicia. Does that sound close to your experience, Frank?

- Frank: Yeah, I guess that sounds about right. It is hard for me to say stuff like that.

- Me: Yes. And that difficulty is creating a lot of static in your relationship with Alicia. How about, Frank, if I try to tell Alicia what you are feeling, as I sense it. I will model it for you. And it will also give Alicia a chance to hear a more detailed articulation of what is going on inside. And if I am off, then you can let me know. Is that cool with you?

- Frank: Yes, you can tell her.

- Me: Alicia, there have been many times over the last several years that Frank has felt that you don’t respect him as a man or a husband. When he makes dinner for you and you don’t thank him. Or when he built the entertainment center and you said it looked “big,” rather than recognizing the craftsmanship that went into it, that hurt. When he asks, “Why are you already in bed under the covers?” he is saying that he wants to be with you physically and when you tell him you are tired and ready for sleep he feels rejected. When you noted that he was not bringing in as much money as he used to and that now you were making more than he, he felt that he lost some worth in the relationship. When you pointed out that he was going grey and balding, he felt you did not desire him. Frank does not know how to tell you these things. Indeed, he does not know how to really feel them himself. Instead, when he feels initially hurt or vulnerable, he then feels anxious and uncertain. And when he feels that way, he quickly justifies why he is his own man, and if it is not good enough for you, then screw you, he will just withdraw to himself. Frank, does that sound about right?

- Frank: Yeah. That about covers it.

- Me (to Alicia): How was that to hear?

- Alicia (with tears welling up inside): I wondered if he felt anything. I felt like he just did not care. Or if he felt anything, it was just annoyed being with me because I was not good enough. A part of me sensed what you are saying, but he never says anything, so I just assumed he did not care.

- Me: He cared alright. It is just that he was defended against putting his vulnerability out there, even to himself.

Frank’s difficulty articulating his inner feelings, especially feelings like hurt or vulnerability—or needs to be held, sexually desired, or admired—is an example of what Levant characterized as normative male alexithymia.

Alexithymia is the clinical-sounding term for when someone has a lot of difficulty translating their emotional experience into words. Normative male** alexithymia refers to the fact that traditional masculine role socialization channels many men into ways of being such that their masculine identity conflicts with many emotions they feel and what they feel they are “allowed” to express (i.e., they will be shamed and will feel as if they are “not real men” if they express feelings of vulnerability, dependency needs, weakness, etc.).

This can create enormous difficulty in relationships because the key variable in guiding couples to come together—or driving them apart, if the need is not met—is each partner’s need to feel known and valued by the other. If either partner cannot put into words their feelings about not being known and valued, but instead hides, defends, or deflects such feelings, then the chances of disharmony and vicious relational cycles are greatly increased.

* As is always the case when writing about clinical encounters on my blog, all names and identifying information and details are changed. The above description represents an amalgamation of themes seen over many years in the clinic room.

** While it is often the case that males experience more difficulty with this (especially traditionally masculine men), it is of course also the case that many women can experience problems with this issue—and that many men are quite competent in sharing their core feelings.